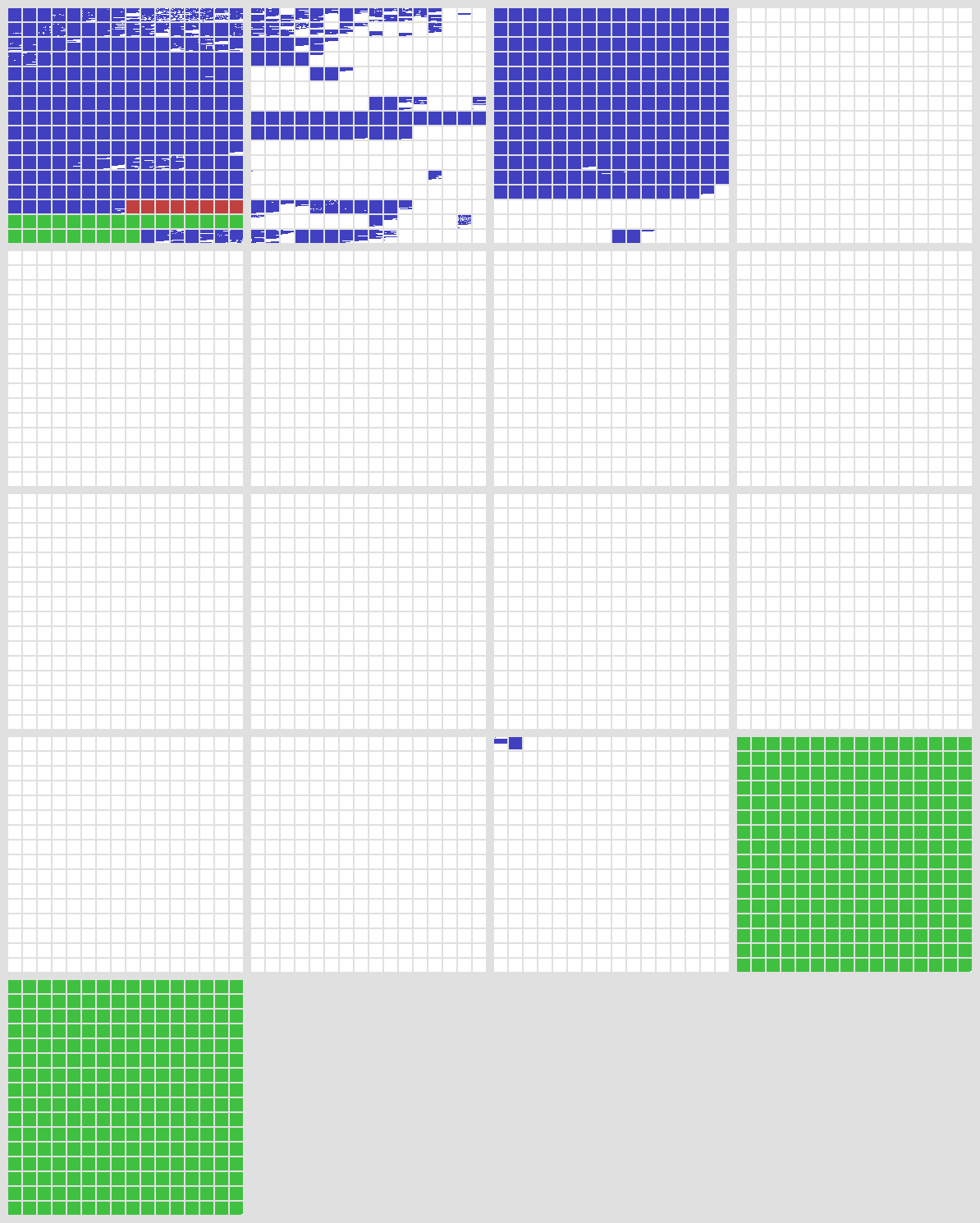

the basic elements of unicode are code points. the set of all possible code points is called codespace. code space is arranged by planes, and there are 17 planes. each plane consists of 256 small squares and each square contains 256 codepoints.

white represents unassigned space. Blue is assigned code points, green is private-user areas, and the small red area is surrogates. as you can see, the assigned code points are distributed somewhat sparsely, but concentrated in the first three planes.

Plane 0 is also known as the “Basic Multilingual Plane”, or BMP. The BMP essentially contains all the characters needed for modern text in any script, including Latin, Cyrillic, Greek, Han(Chineses), Japanese, Korean, Arabic, Hebrew, Devanagar(Indian), and many more.

(In the past, the codespace was just BMP and no more–Unicode was originally conceived as a straightforward 16-bit encoding, with only 65,536 code points, It was expanded to its current size to in 1996, However, the vast majority of code points in modern text belong to the BMP.)

Encodings

We’ve seen that Unicode code poins are identified by their index in he code space, ranging from U+0000 to U+10FFFF. But how do code points get represented as bytes, in memory or file?

the most convenient, computer-friendliest(and programmer-friendliest) thing to do would be to just store the code point index as 32-bit integer. This works, but it consumes 4 bytes per code point, which is a sort of a lot.

Consequently, there are serveral more-compact encodings for Unicode. the 32-bit integer encoding is officially called UTF-32(UTF=”Unicode Transformation Format”), but it’s rarely used for storage. At most, it comes up sometimes as a temporary internal representation, for examining or operating on the code points in a string.

Much more commonly, you’ll see Unicode text encoded as either UTF-8 or UTF-16. There are both variable-length encodings, made up of 8-bit or 16-bit units, respectively. In these schemes, code points with smaller index values take up fewer bytes, which save a lot of memory for typical texts. The trade-off is that processing UTF-8/16 texts is more programmatically involved, and likely slower.

UTF-8

In UTF-8, each code point is stored using 1 to 4 bytes, based on its index value.

UTF-8 uses a system of binary prefixes, in which the high bits of each byte mark whether it’s a single byte, the beginning of a multi-byte sequence, or a continuation byte;the remaining bits, concatenated, give the code point index.

Combining marks

In the story so far, we’ve been focusing on code points, But in Unicode, a “character” can be more complicated that just an individual code point!

Unicode includes a system for dynamically composing characters, by combining multiple code points together. This is used in various ways to gain flexibility without causing a huge combinatorial explosion in the number of code points.

In European languages, for example, this shows up in the application of diacritics to letters. Unicode supports a wide range of diacritics, including acute and grave accents, umlauts, cedillas, and many more. All these diacritics can be applied to any letter of any alphabet– and in fact, multiple diacritics can be used on a single letter.

Canonical Equivalence

In Unicode, precomposed characters exist alongside the dynamic composition system. A consequence of this is that there are multiple ways to express “the same” string–different sequences of code points that result in the same user-perceived characters.

Unicode refers to set of strings like this as “canonically equivalent”.

Normalization Forms

To address the problem of “how to handle canonically equivalent strings”, Unicode defines serveral normalization forms: ways to converting strings into a canonically form so that they can be compared code-point-by-code-point.

The “NFD” normalization form fully decomposes every character down to its component base and combining marks, taking apart any precomposed code points in the string.

The “NFC” form, conversely, puts things back together into precomposed code points as much as possible.

Grapheme Clusters

As we’ve seen, Unicode contains various cases where a thing that a user thinks of as a single “character” might actually be made up of multiple code points under the hood. Unicode formalizes this using the notion of a grapheme cluster: a striing of one or more code points that constitute a single “user-preceived character”.